Steppe Nomads

November 2025

Fine

September 2025

Anarcho Capitalism

June 2025

Seers

May 2025

Karsaga Reach

April 2025

Dover Scavs

March 2025

Druids

February 2025

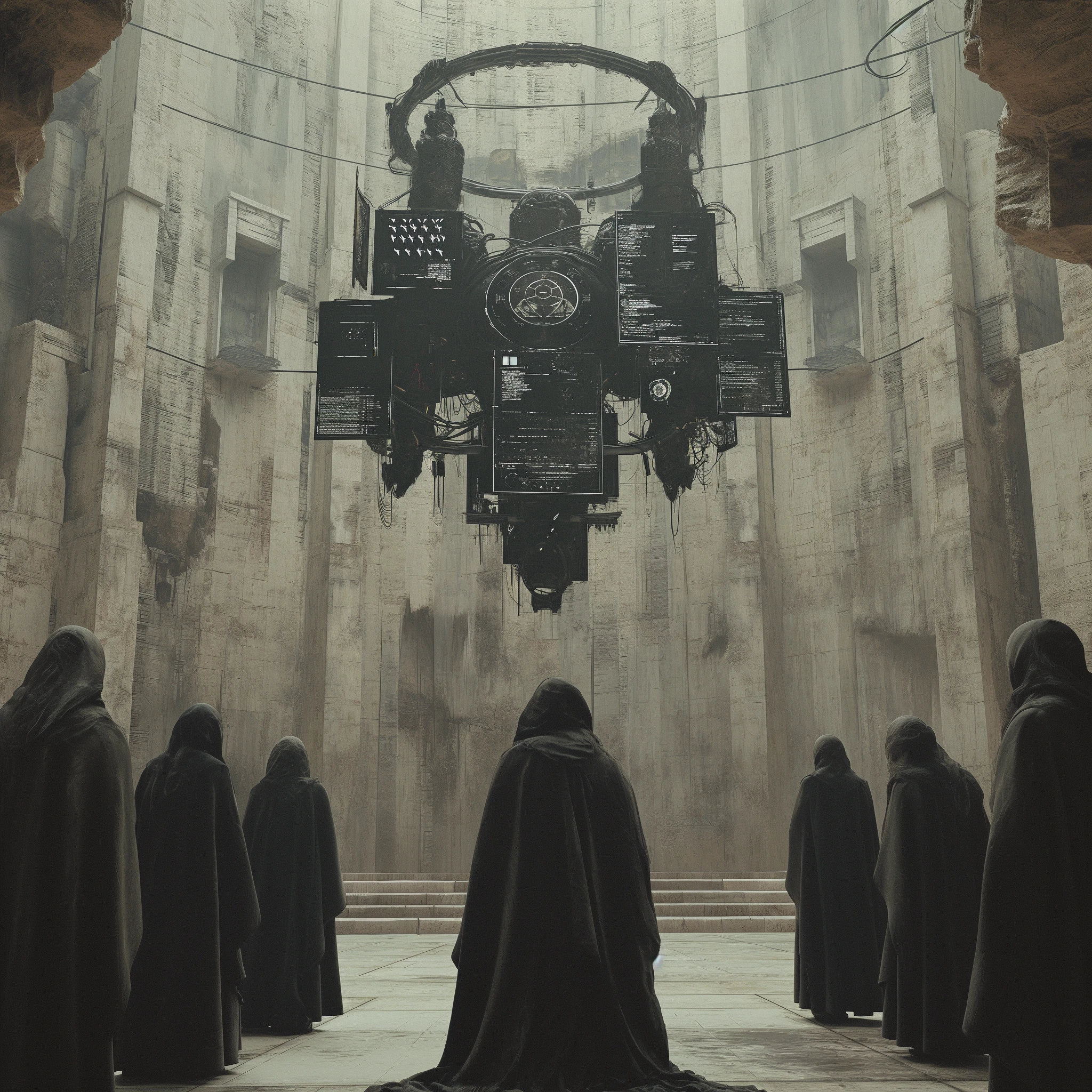

Oracle

October 2024

Jesuits

September 2024

Resistance

August 2024

Lord Of Light

June 2024

Cage Of Souls - Chapter 2

April 2024

Cage Of Souls - Chapter 1

March 2024

DSP

March 2024

Five Views of the Planet Tartarus

February 2024